“TREMOR: WILL, DIFFICULTY, AND ANTAGONISM”

Selections from “Estremecimiento: Voluntad, dificultad y antagonismo,” (pp. 97-188), second chapter of Estallido: La Rebelión de Octubre en Ecuador, by Leonidas Iza, Andrés Tapia and Andrés Madrid (Quito: Ediciones Red Kapari, 2020).

Translated by Jaime R. Brenes Reyes

“Si no hay solución, ¡habrá una Revolución!”/ “If there’s no solution, there’ll be a Revolution!” (96)

Red Kapari is a grassroots alternative communication network in Ecuador, which produces content that makes visible the social struggles born from the popular sectors and the Ecuadoran Indigenous movement. “Kapari” is a word from the Kichwa language that translates as “shout.” Its main objective is to “create a communication network for and by the working class,” against elite and mainstream media. The Red Kapari organizes itself in cooperative assemblies and intends to show that “another journalism is possible.” Its prolific content, which includes regular news and opination articles, photo essays and videos, can be found in their online channels.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RedKapari

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/RedKapari/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/RedKapari

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3JDC9EwB52eq7LlU5dtUIQ

Introduction

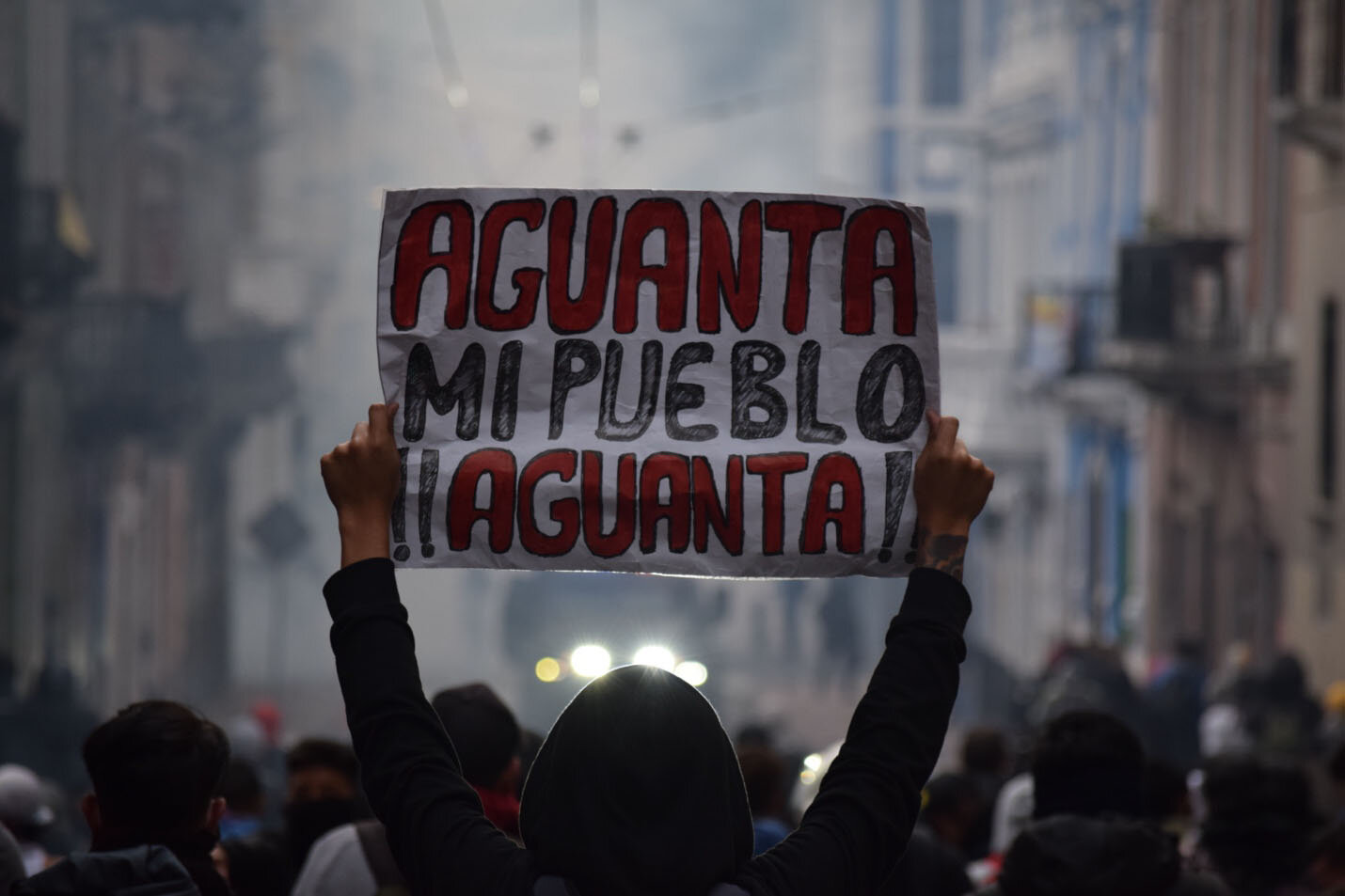

October 2019 marked a historic moment in Ecuador. Nationwide, massive mobilizations took the streets in a reclamation of justice. The protestors were the marginalized: Indigenous and Black people, with the support of the urban-middle class. Red Kapari has generously allowed us to translate and use material from their recently published book Estallido: La Rebelión de Octubre en Ecuador / Explosion: The October Rebellion in Ecuador (Quito, 2020), which recounts and analyzes these events.

In this piece, we present passages from the second chapter, “Estremecimiento: Voluntad, dificultad y antagonismo” / “Tremor: Will, Difficulty, and Antagonism” (pp. 97-188), written by Leonidas Iza, Andrés Tapia and Andrés Madrid. We selected this chapter to highlight the conflict of big, mainstream media versus alternative and community-based media during the October Rebellion that shook Ecuador in 2019. We pay special attention to the use of online platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, as well as of end-to-end encrypted communication, e.g. WhatsApp.

To give some context, the mobilizations began on October 3, 2019, when the Ecuadoran government announced an increase in the price of fuel as per the Decree 883, signed by president Lenín Moreno. The decree was part of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The increase in the price of fuel shocked the country. Actions took place within hours. The drivers’ union called for a national strike. The “Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador” (CONAIE, Spanish abbreviation for the “Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador”)[1] already had a series of protests scheduled for mid-October (101). Rapidly, “The national transport strike took Ecuadorans to the streets and forced to move the mobilizations two weeks earlier in October” (130).

Why such an explosion from the signing of the Decree 883 and the drivers’ response? As the authors point out, “the paralysis of [the driving] service vitally affects the circulation of capital” (130). The strike hit the right point at the right time. As the drivers paralyzed the country, the Indigenous movement took the lead and became the voice of the people (97-8). Importantly, within days the drivers’ signed a deal with the government. However, that did not stop the mobilizations, which included many drivers that remained committed to the Uprising. The CONAIE acted as an anti-capitalist organization “at heart [with] national presence” (97).

According to the authors, in October 2019, Ecuador witnessed “the largest rebellion in [the country’s] recent history” (100). More than 50,000 Indigenous people took over Quito for a period of eleven days and established the “Quito Commune” (241).

Brief timeline of the October Rebellion

October 3: First self-organized protests in Quito’s downtown, the “first symptom of the Rebellion to come” (102). From the very first day there is resistance against police brutality.

October 4: “National mobilizations” take place with “281 points” across the country (102). Police brutality increases.

Weekend of October 5-6: Plans for “la toma de Quito” (“the take-over of Quito”) begin to form. The drivers’ union strikes a deal with the government; however, not all drivers follow their leaders. “Mainstream media and the government hide the Indigenous uprising and the national strike, claiming that it is only a transport strike” (99).

October 7-10: Quito is taken over as the Indigenous people enter the city, the national mobilization solidifies, and strategic positions in Quito are defended by the people (104). People in the city confront the police so that those coming from the rural areas can enter. Caring and gathering centres expand, with many staying at the “Casa de Cultura Ecuatoriana” (“Ecuadoran Culture Centre”) (104). Solidarity is evident. Police action intensifies in other provinces as the media focuses on Quito (105). The government moves to the coastal city of Guayaquil, a conservative leaning city. The move does not succeed in bringing ‘normality’ and ‘stability’ as the mobilizations expand to the seaside regions of the country. There was self-convocated, “overarching,” popular support. (99-100). Mainstream media does not report on the real numbers.

“The Quito’s march was one of the wider in the history of Ecuador.” “CONAIE overpassed their expectation.” “50,000 Indigenous people arrived in Quito.”

October 8: The protestors enter the National Assembly, “a loud bell of the Rebellion force” (106).

October 11-13: Of “vital importance to the Resistance [is] arrival of reinforcement from the Andean and the Amazon provinces.” The main focus of Resistance is the area surrounding the strategic point of ‘El Arbolito,’ located near the National Assembly and the main streets in Quito’s downtown (109).

On October 11, at ‘El Arbolito,’ “police officers were waving white flags, a truce that was accepted and acknowledged. Thousands of men, women, elder and children surrounded the building and shared food with the security guards … However, the police agents attacked after a fleet of helicopters provided them with supplies, attacking people with an intense discharge of tear gas.” “Activists and community-based media considered the tactic an ambush.” (109-110)

October 12: A feminist march takes the streets to repudiate the colonial tradition of celebrating October 12th as the ‘Día de la Raza,’ which covers up the invasion of the Indigenous lands of the Abya-Yala. The statue of Queen Elizabeth II is covered in red paint.

Same afternoon, the government announces a curfew. It is “important to emphasize that it was the first curfew since the return to democracy” (110). In response, people self-organized a ‘cacerolazo,’ “which in many areas became marches and protests” (110).

People’s chant: “Toque de queda, toque de Resistencia” / “To the curfew, resistance!” (110).

By the evening, the government and the CONAIE agree to negotiate. “The Indigenous movement served as a representative on behalf of all that had taken part in the conflict” (110).

To put the government to negotiate with the Indigenous movement is considered a “historical victory.” “Those in power received a slap in the face, transmitted live in national and international media” (110).

“Se negocia con barricadas encendidas” / “[real] negotiations are with lit barricades” (111)

What follows is a translation of two important sections from “Estremecimiento: Voluntad, dificultad y antagonismo”, Chapter 2 of Estallido: La Rebelión de Octubre en Ecuador.

The Control of the Official Discourse

“The dispute of discourses – the battle of ideas – is in the end a fight about how to read history.” “The October conjuncture was different [from the norm]. The ruling class had poor capacity to misconstrue reality, to interfere in the will of others and, more importantly, to control the denouement of the conflict” (171-2)

The discourse of the bloc that defended Moreno became a request to the people for ‘comprehension,’ an attempt to minimize the scopes of the protests, an invocation to peace, and, finally, a witch-hunt.

On such a path, the management of language signals a shift towards the right. Expressions like ‘we call for social peace,’ and ‘guarantee democracy,’ and references to ‘subversive cells’ and ‘gathering centres’ became common. Mainstream media systematically continued a discourse inciting hate.

In fact – gradually, at the beginning of the protests, and then all at once in the last days of the uprising and afterwards – the editorial line of mainstream media broke-out in a plague of calls for the State to escalate violence.

Hand in hand with this repertoire, the stigma of disparagement jutted out against Indigenous and Black people, separating them from the different nationalities of Ecuador … Some analysts and journalists defended the racist idea of an ‘electoral manipulation’ of the Indigenous movement or of a ‘continental conspiracy,’ aberrations that discarded any possibility of an autonomous initiative by the Indigenous people … This reproduced in a new scenario the discourse of the Rousseaunian ‘good savage,’ which frames the oppressed as incapable of rebelling because of their natural and social condition.

Such references affirm that the poor are ungrateful, incapable and docile. What troubles those in power is not the ‘destruction’ of the Indigenous heritage, but rather its irruption in the space of the ‘whiteness’ and the ‘whiteful’ idealized in the montage of the imaginary Nation.

There was a bias in the diffusion of information. Images that supported the discourse of violence were privileged. Any mention of the people’s self-defence against State violence was neglected. The pattern of conduct of the repressive forces was presented only at the margins. The police raids, purposely, were conducted after the end of the primetime TV News [5pm], so that the most aggressive cases of repression were not shown on the news.

Additionally, the hegemonic communication outlets neither condemn nor question the systematic calls from the right-wing to subvert the situation and take violence into their own hands.

Censorship was increasingly applied against media that were more closely following events and broadcasting in a way that took into account the protestors’ opinion. For example, people that were speaking against the government had the microphone turned off during reports. Instead, media outlets opened themselves to what the official line termed ‘protesters for peace,’ some of whom fiercely rejected the ‘thuggish and ill-mannered Indians.’ Or they engaged in ‘constructive’ binge broadcasting: on October 12, SpongeBob was on air for 4 hours and 35 minutes on Teleamazonas, while Ecuavisa transmitted a soap opera. One more indicator: how many times is an Indigenous leader interrupted during a live interview? And how many times does the same happen to someone who represents the ruling class?

Radio Pichincha Universal, one of the few media outlets that publicly aligned with the Rebellion, was raided after some unknowns cut their electricity. The radio’s audience grew exponentially, reaching 6.5 million on Twitter and 5.8 million on Facebook. Digital media websites such as Zángano Press and Wambra Radio were disrupted. Telesur was removed from cable TV; the TV channels RT and HispanTV were censored, as well as three journalists and three columnists of the public newspaper El Tiempo of the Cuenca province. There was a lack of safety that impeded journalistic work, especially that of community-based media.

The indiscriminate blockade, the hacking and the temporal suspension of the social media accounts of community leaders and organizations, the trolling attacks, and the use of mobile phone jammer to reduce the connectivity in the Agora of the Ecuadoran Cultural Centre were all part of the media state of exception imposed by the State ideological apparatus.

Systematic defamation was central to the campaign conducted by mainstream media, which published headlines such as ‘The CONAIE sees racism even in a bowl of soup,’ ‘Violence: CONAIE unpunished,’ ‘The country walks towards peace, the indigenous towards violence,’ and ‘Vandalism leads the indigenous movement.’

The media discourse followed a war-communication model. Such a model partly accepts the total war doctrine included in the White Book, the manual that dictates the national defense policy of the Ecuadoran State. The communication action of the hegemonic media is a part of the loud and insidious combat program against the subaltern.

Thus, October 2019 taught us a big lesson: so-called ‘freedom of speech’ does not exist. Beyond juridical formalities, freedom of speech is, in real terms, a ploy to legitimate the take over of discourse through the use of power. Different arguments are indeed expressed, generally, within an apparent debate over truth and power. But in such a debate, the ideas that have more access to resources and capital are in a privileged position to win the dispute. Along this line, we ask: what are the legal and de facto criteria to guarantee the right of the social classes that do not possess the capital and resources to express their opinion publicly?

Yet, despite the media blockade, the October Rebellion won many victories in the battle of ideas. First, the Government’s communication strategy failed: popular acceptance fell to 15.4%, reaching its lowest point at 8%. However, even though this was a success, it also showed the level of the social support that, in moments of increasing confrontation, continued to align itself with conservatism and the preservation of the normal state of things.

Second, in spite of the media concealment of events, the growth of the mass mobilizations over a period of eleven days had an impact on common sense, which – as Gramsci argues – is the habitat of the ruling class’s ideas. Thus, according to surveys, from October 5 onwards most of the population disagreed with the elimination of the gas subsidies. By October 11, 92% of the households were closely following the conflict; 76% were calling for an urgent solution.

Third, the skewed position of mainstream media was more than evident. The result was that 86% of people expressed that the events that took place during the mobilizations were censored by the communication emporiums. This led to a profound questioning of the hegemonic media.

The Hidden Stories that Silenced the Official Discourse

The protests questioned the mainstream media’s practice of presenting reality according to their interests. Consequently, big media lost their ‘unquestionable credibility.’ Slogans such as ‘what is it that you don’t see on the news’ and ‘the media isn’t saying what’s happening in the country’ proliferated.

One of the fetishes for political legitimacy is the ‘defense of democracy.’ This is a discourse that the capitalist media also used as a shield – because companies also fabricate shields – to not transmit information from the popular sectors, even though, theoretically, the idea of democracy is associated to popular sovereignty. If the mainstream media version of democracy is dissociated from popular uprisings, should we consider that big media was ‘against’ democracy when they supported the mobilizations that caused the dismissal of [six] presidents during the 1997-2005 period?[2]

According to a survey conducted by CEDATOS (2019), media companies were seen negatively by most of the population: 43.4% positive against 47.7% negative. Meanwhile, international media agencies had to sort out how to get around the media fence in order to access information about the October 2019 events.

Additionally, for the first time in Ecuador social media became a resource with significant media influence by reproducing versions of reality more in touch with the needs of the majority of the people, those that were part of the October Rebellion. Community-based and alternative media were the first to use online platforms. As the mobilizations extended and intensified, self-organizing groups multiplied the usage of social media. According to Castro and Tapia (2019), more than 50% of the sources of information during the Rebellion came from online channels: 31% Facebook, 13% digital media, 4% WhatsApp, 1% Twitter. This is in comparison to the 47% that were ‘informed’ by TV. On the whole, online platforms surpassed TV as a source of information.

In order to reverse the media information bias, people pressed the hegemonic media to transmit events without editorial filters. This tactic emerged after the first round of extrajudicial executions, which murdered protestors. On October 10, by resolution of a popular assembly, the media had to stay for seven hours in the Agora of the Quito’s Culture Centre, forced to livestream the funeral of Inocencio Tucumbi, an Indigenous leader murdered by the police the previous night. As the magazine Plan V reported:

Some journalists reported entering and leaving the site without any problems [and that] inside the building they were offered food and water. They were also guaranteed safety and help with recharging their equipment for the transmission of the events. All that the people demanded was for ‘everything’ to be transmitted as it was happening. The organizers were monitoring the public and private TV channels. ‘It is live’, ‘it is not live’ the Indigenous organizers would tell the journalists [to make sure they were transmitting]. (2019)

The corollary of this process was that the dialogue between the CONAIE and the Government had to be televised on live TV. In this context, the October Rebellion put, on one side, all the representatives of the Government and, on the other, the leaders of the Indigenous movement on behalf of the people in rebellion. The dialogue was a ‘deep breath’: it was the popular organizations’ major victory against the government in the history of the country.

As the dialogue was taking place, memes were spreading through social media. Someone commented: ‘it looks like a reality show: on one side of the table, the people that can barely express themselves, speak Spanish very badly and one cannot understand what they’re saying. On the other side of the table, the Indigenous people.’ (Herrera, 2019)

The temporary halt to competition among big media demonstrates the homogeneity of their editorial stance, another lesson from October 2019. The differences among the sectors of the ruling class became secondary. However, the military logic adopted by the official media, as well as the censorship of alternative platforms, made people demand changes. By contrast, journalists working in the neighbourhoods and communities did not face any violence or hostility. Indeed, many alternative and community-based media reported feeling safe among the protestors. Is it not an aggression to repress freedom of speech or to use war communication tactics against the mobilizations of the exploited classes?

The events and the journalism produced by the alternative and community media broke into the battle of ideas, countering official media. Thus, the questioning of neoliberalism enlarged: between 60% and 70% of the people considered that the agreement between the Government and the IMF was harmful. According to surveys, 87% agreed that the mobilizations were necessary, and only 12% did not agree (KolectiVOZ, 2019).

The legitimacy of the mobilizations, at the national level, led to a large and combative participation of the exploited classes. In Quito, around one million people participated directly in the protests, and around one million and a half supported them. The decision by the popular organizations to push for a process of struggle against the Government broke a tendency towards apathy in the political practice of the people.

Upon analyzing the people’s perception about the protesters and their organizers, the presence of the Indigenous movement and of the popular organizations is vindicated. In other words, a positive image of the movements and organizations, damaged many times over recent years, grew exponentially. The demonstrations drew sympathy. According to ‘Perfiles de Opinión,’ 84% of the people in Quito and Guayaquil declared that the Indigenous movement defended the rights of all peoples, and only 16% thought that they were defending their own interests (in KolectiVOZ, 2019). Of those that did not participate in the mobilizations, half did so because of fear to State repression or from their employers. Divided by levels of income, those with high-medium income split evenly in support or against the protests. However, a vast majority of those with low-medium and low income said that the Indigenous defended the rights and interests of all peoples. Therefore, we conclude that processes of struggle construct political identities among the poor.

In the battle of ideas, the ruling class’s major concern is not the labour conditions of those that work in the media companies – long shifts, workplace hazards, and, very often, precarious working conditions; rather, the ruling class wants their media hegemony not to be challenged. The percentage of people that declared they did not to trust media such as TV channels has increased over the years and increased even more during the October Uprising.

Although the statistics show a high level of rejection of the order of things, it would be erroneous to think that October 2019 transformed ‘common sense’ completely or that it consolidated a long-term counterhegemonic strategy. Thus, the CONAIE’s main objective, formulated in their manifesto previous to October, was only partially achieved: ‘to advance actions that allow the achievement of major victories for the exploited classes: workers, campesinos, women, students, youth, artists, and all nationalities and peoples of Ecuador.’ It was only partially achieved because it did not consolidate a medium-term agenda – even less, one for the long term.

People’s common sense, in general, continues to be conservative, even after a period of post-neoliberalism [Translators note: ‘post-neoliberalism’ is a term used in South America to refer to the ‘pink tide’ of leftist governments such as those of Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, and, by some estimates, Rafael Correa, a previous President of Ecuador]. The nucleus of ideas that form the popular repertoire still reproduces hegemony. Reviewing most of the debates during and after the October Uprising, it seems as if the country’s economic problems are all about the budget deficit – the so-called fiscal crisis. These discussions push to the margins the issue of the bourgeoisie’s direct interference in the economy, and most debates make few references to the structural, integral, and social crisis of modern capitalism.

The true hegemonic nucleus of Ecuador is not, as some believe, just ‘anticorreísmo’[3] [Translator’s note: hostility to the previous left-leaning president, Rafael Correa] – an idea that is barely a slogan as elections now approach.[4] Rather, to break the ideological and cultural patterns that allow the reproduction of domination requires surpassing a comprehension of reality that is limited to a dichotomy: statism/neoliberalism.

---

Translator’s Conclusion

The post-October 2019 scenario is still unfolding in Ecuador. As the translation of this chapter proceeds, the country held presidential elections on February 7, 2021. To the surprise of many, the elections saw Pachakutik – not directly, but closely related to the CONAIE – gained far larger support than had been anticipated. But whatever the outcome of the elections, we emphasize a basic point: the October Rebellion marked a “before” and an “after” in Ecuadoran politics, with effects that are still unfolding. Will the presidential elections see a victory for the Indigenous movement? It is hard to say. Going by perspective of the Red Kapari authors, participating in electoral democracy does not directly lead to a victory. Instead, they propose a radical change in which Ecuadorans continue the ‘battle of ideas’ that would change ‘common sense.’ They believe it is necessary to stop the control of discourse by the business elite. Undoubtedly, the Ecuadoran Rebellion is part of a much larger movement that has escalated to global proportions – a series of uprisings in different nations that is showing that politics can be different, not necessarily by electoral modus operandi, and with online platforms as a key element. We are witnessing new processes of struggle, such as those currently underway in Myanmar and India, and a global movement of uprisings.

References

Castro, Apawki y Andrés Tapia. 2019. Ataques, vulneraciones y cerco mediático al movimiento indígena durante el paro nacional. https://www.alainet.org/es/articulo/203809

CEDATOS. 2019. Evaluación del paro nacional.

Herrera, Stalin. 2019. “El movimiento indígena y la insurrección de los zánganos”. https://lalineadefuego.info/2019/10/22/el-movimiento-indigena-y-la-insurreccion-de-los-zanganos-por-stalin-herrera/

KolectiVOZ Digital. 2019. PARTE 2 - FORO en Quito: Protesta, ajuste y política. Escenarios post-octubre. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmAMTU78vvA

Plan V. 2019. Conaie: en el Ágora se dio la rebelión de las bases. https://www.planv.com.ec/historias/politica/conaie-el-agora-se-dio-la-rebelion-bases

Notes

[1] N.B.: Ecuador declares itself a “pluri-national country.”

[2] Abdala Bucaram (August 10, 1996 – February 6, 1997); Rosalía Arteaga Serrano (February 9, 1997 – February 11, 1997); Fabián Alarcón Rivera (February 11, 1997 – August 10, 1998); Jamil Mahuad Witt (August 10, 1998 – January 21, 2000); Gustavo Noboa Serrano (January 22, 2000 – January 15, 2003); Lucio Gutiérrez Borbúa (January 15, 2003 – April 20, 2005).

[3] Those against former president Rafael Correa.

[4] The elections took place on February 7, 2021, as this translation was in process.

![“Total war strategy – orchestrated by the Defense Ministry, Oswaldo Jarrín [meant] subordination – of the political, financial, psychological, institutional and constitutional resources of the government and the elite – to the Army.” (156)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f34350398629d0bc08589d9/1628866582871-IXE2L3MKAG44OK61EPUV/RK_5.jpg)

![“According to the CONAIE, the repression left a total of 11 people dead, 1,700 wounded, 1,250 detained and hundreds of ‘perseguidos,’ [prosecuted, harassed] 90% of which were arbitrarily and illegally detained. All these took place in a context of m](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f34350398629d0bc08589d9/1628866583324-GD9BNP6L6QPC1NEQTX8N/RK_7.jpg)